A cemetery with galleries

A severe demographic crisis affected Europe in the 14th century. War, famine and the Black Plague in the south of France from 1347 decimated the population. The city of Rouen was also badly affected.

In the busy parish of Saint-Maclou, the cemetery next to the church quickly became too small for the number of dead. So in the mid-14th century, a new cemetery was created. It became the “large ossuary”, as opposed to the church’s “small ossuary”.

What is an ossuary?

In the Middle Ages, the population used the terms “ossuary” or “charnel house” to refer to a cemetery. The term “cemetery” was learned language used by the clergy.

The ancient French word for ossuary – aître – comes from the Latin atrium. In Roman times, it referred to the inner courtyard of a home surrounded by a gallery supported by columns. Over time, the term atrium was used to refer the church’s courtyard which gradually became a cemetery.

New waves of plague affected the city of Rouen, during the 15th and 16th century in particular. Yet again, the new ossuary became too small to deal with the large numbers of deaths in the parish of Saint-Maclou, despite numerous expansions throughout the 15th century.

In 1526, the parish decided to build three galleries around the cemetery to store the bones. In order to create space for new burials, the bones of the dead were disinterred and placed in these galleries, in the attics, well ventilated and in view of everyone.

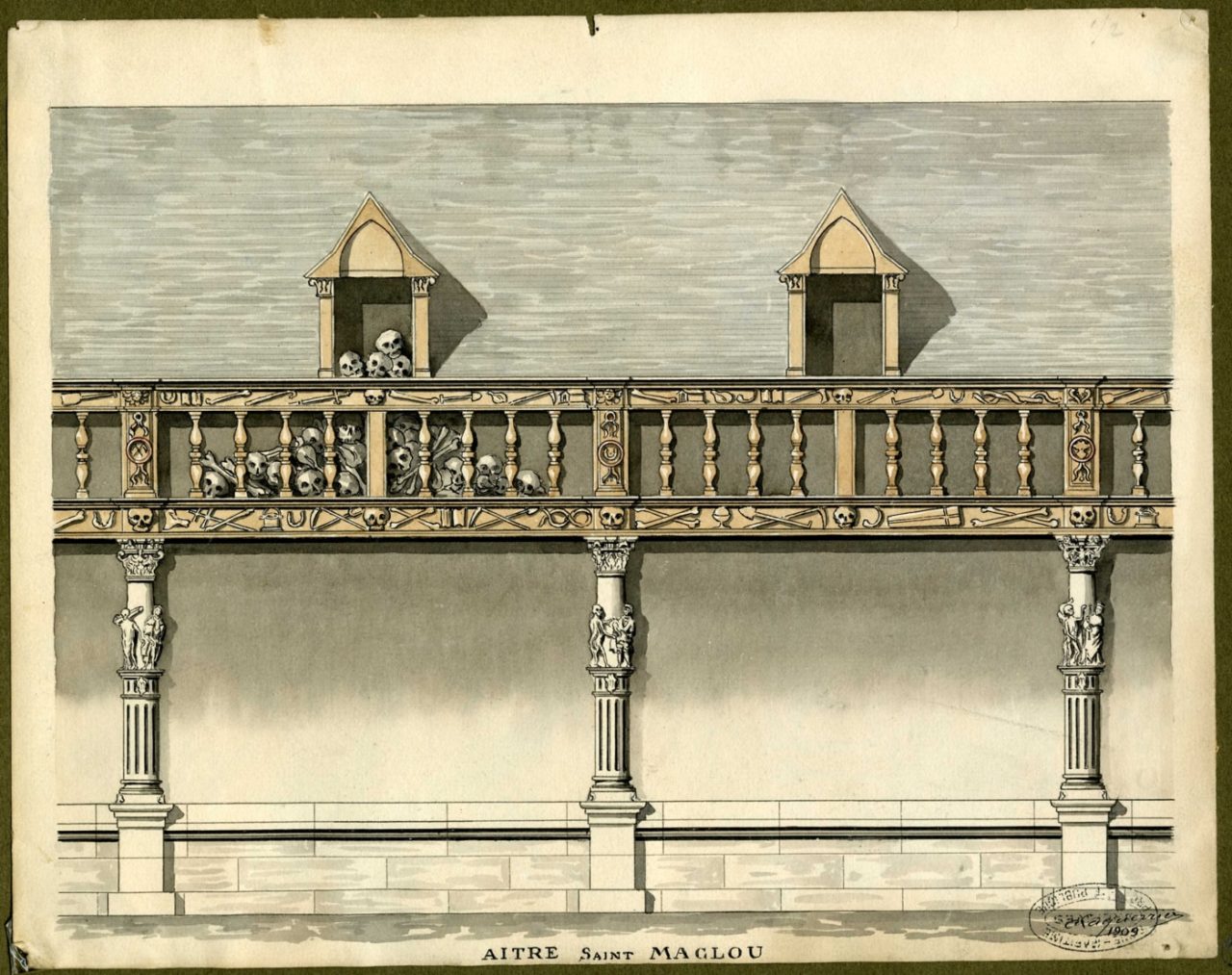

This is a suggested elevation view of one of the galleries in the 16th century. Various questions not resolved by archaeological research remain unanswered: how were the attics accessed? Were there dormers?

These galleries are adorned with wooden and stone parts with ornate and macabre decor.

Danse macabre

A danse macabre is depicted on stone columns which support the floor of the attics.

In the west gallery, we can see the danse macabre of laypeople (Emperor, king, aristocrats, etc.) positioned hierarchically and on the east gallery, members of the clergy (pope, bishop, monk, etc.). Each column depicts a pairing made up of a dead person and a living person. The resigned or frightened living person is hanging onto the dead, who takes them to their inevitable demise.

What is a danse macabre?

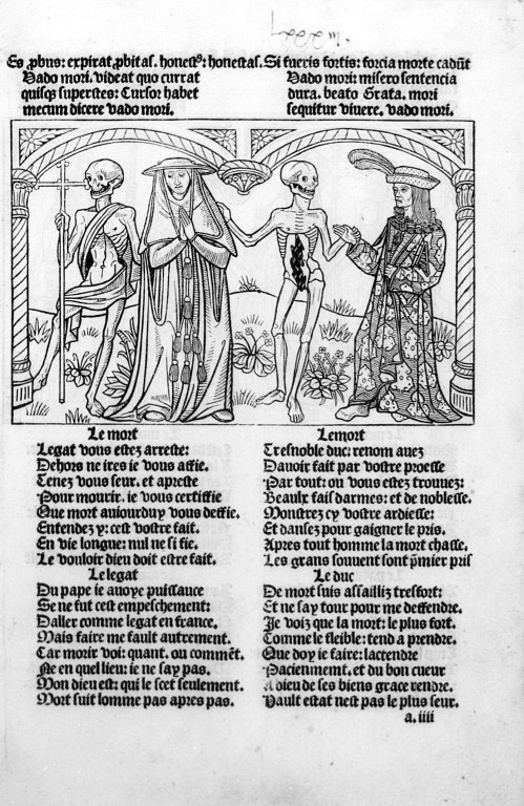

At a time when death was so prevalent, there was an increasing amount of macabre motifs used in literature, painting, engravings, sculptures and even everyday objects. Amongst these motifs, one of them spread throughout Europe in the 15th century: the danse macabre.

This dance of the dead is a march, a tour representing people from Medieval society, across all social classes. Each of them is led by death personified by a skeleton or a cadaver: no one can escape it. The danse macabre has a Christian message: prepare to face God on judgement day, in the hope of a better eternal life.

The recently restored danse macabre at Aître Saint-Maclou is now one of the most beautiful examples of sculpted dance in Europe.

In the north part of the ossuary, on the north-west and north-east pillars, man’s death is depicted in its original Christian form: the original sin with Adam and Eve. The north-east column represents the first murder in human history: Abel by Cain.

A series of columns in the north gallery depicts pairs of sibyls, female oracles announcing the coming of Jesus Christ.

The wooden beams which frame the floor of the attics are also sculpted with macabre motifs. All sorts of human bones are represented (skull, femur, jaw) but also gravedigger’s tools (pick, shovel, coffin) and liturgical instruments used during burials (font, wafer box, sprinkler, prayer book).